Kidney Worms cause an unthrifty appearance, slow growth, poor feed conversion and occasionally death.

Wooded lots and shaded farrowing pens often become contaminated areas where larvae hatch from eggs and enter the soil. Pigs may become exposed to infective larvae by ingestion, skin penetration, and ingestion of infected earthworms. Larvae then move from the small intestine and eventually into the liver, where they remain for two to four months. Other organs such as the lungs and spleen may also be infected. From the liver, larvae migrate to areas around and in the kidneys and even into back muscle. Most of the damage is found in the liver, which becomes heavily scarred, and in nearby muscle tissue.

Large Roundworms are a common parasite infecting pigs. The adult parasite is a long white worm similar in size/shape to a spaghetti noodle. This parasite is zoonotic, it can be passed between pigs, humans, and other pets. Even single pig households are susceptible to large roundworms. A. suum eggs are extremely hardy and can survive for as long as 15 years in the environment. They remain viable in swine effluent water for at least 14 months. The eggs can be transported by infested pigs, insects, fomites, blowing dust, pig manure, and effluent. Symptoms or complications of roundworm infestation will not show until the parasite has taken a significant toll on your pig's health. Roundworms can cause pneumonia, unthriftiness, failure to gain weight, rough hair coat, intestinal blockage, pendulous abdomen, chronic paroxysmal coughing and occasionally, abdominal expiratory dyspnea (“thumping”). Heavy infections can result in hundreds of ascarids in the intestine of a single pig. The eggs are ingested then hatch in the intestine, the larvae migrate through the wall and via the blood enter the liver. They then migrate through the liver to the lungs, finally reaching the trachea where they are coughed up, swallowed and returned to the small intestine to develop into adults. Large Roundworms are easily treated with ivermectin or fenbendazole.

Thread worms occur commonly in baby pigs. The adults are practically microscopic and live in the wall of the small intestine. Heavy infections may cause intensive scouring in neonatal pigs, resulting in acute dehydration. The threadworm (aka Strongyloides) lives in soil contaminated by infected feces. Unlike the other round worms of the intestine the threadworm larvae enter the pig by penetrating the skin or mucous membranes of the mouth and are transported by the blood to the lungs, coughed up and swallowed. They then develop to maturity in the small intestine. The infective larvae can also cross the placenta or be excreted by the colostrum and therefore infect piglets within 24 hours of birth. The prepatent period is from 3-7 days. Strongyloides ransomi is also particularly harmful for piglets. Massive infections cause hemorrhagic or mucous diarrhea, anemia and even sudden death. Other symptoms include coughing and abdominal pain.

Whipworms are another common parasite in pigs. This is another zoonotic parasite that can be transmitted to humans and other pets. In the United States, whipworms were one of the three most prevalent internal parasites of swine. The pigs pickup this parasite while grazing or rooting in the dirt. The adult worms are 5–6 cm long and whip-shaped; the anterior slender portion embeds within the epithelial cells of the large intestine, especially the cecum, with the thickened posterior third lying free in the lumen. Damage occurs to the pigs intestines with inflammation and lesions. Weight loss and diarrhea are symptoms of a whipworm infestation. Whipworms are easily treated with fenbendazole. Ivermectin has been used for whipworms with varying success.

External Parasites

Biting insects (hematophagous), i.e. they suck blood

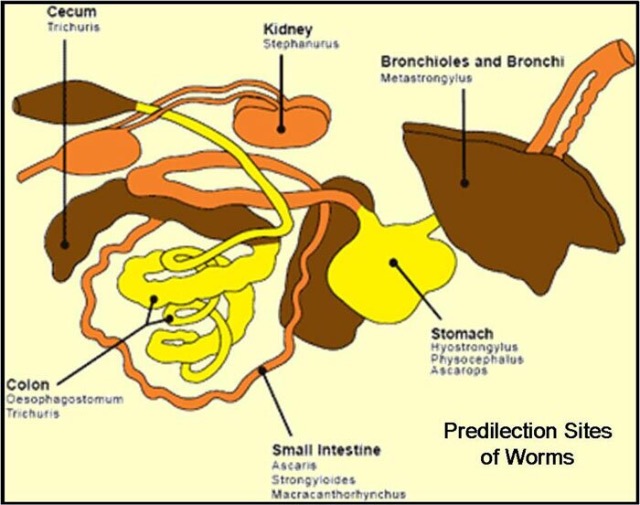

Internal parasites

(endoparasites, worms, helminths)

The parasites' preferred location sites are indicated in brackets.

Gastrointestinal roundworms (nematodes)

Wooded lots and shaded farrowing pens often become contaminated areas where larvae hatch from eggs and enter the soil. Pigs may become exposed to infective larvae by ingestion, skin penetration, and ingestion of infected earthworms. Larvae then move from the small intestine and eventually into the liver, where they remain for two to four months. Other organs such as the lungs and spleen may also be infected. From the liver, larvae migrate to areas around and in the kidneys and even into back muscle. Most of the damage is found in the liver, which becomes heavily scarred, and in nearby muscle tissue.

Large Roundworms are a common parasite infecting pigs. The adult parasite is a long white worm similar in size/shape to a spaghetti noodle. This parasite is zoonotic, it can be passed between pigs, humans, and other pets. Even single pig households are susceptible to large roundworms. A. suum eggs are extremely hardy and can survive for as long as 15 years in the environment. They remain viable in swine effluent water for at least 14 months. The eggs can be transported by infested pigs, insects, fomites, blowing dust, pig manure, and effluent. Symptoms or complications of roundworm infestation will not show until the parasite has taken a significant toll on your pig's health. Roundworms can cause pneumonia, unthriftiness, failure to gain weight, rough hair coat, intestinal blockage, pendulous abdomen, chronic paroxysmal coughing and occasionally, abdominal expiratory dyspnea (“thumping”). Heavy infections can result in hundreds of ascarids in the intestine of a single pig. The eggs are ingested then hatch in the intestine, the larvae migrate through the wall and via the blood enter the liver. They then migrate through the liver to the lungs, finally reaching the trachea where they are coughed up, swallowed and returned to the small intestine to develop into adults. Large Roundworms are easily treated with ivermectin or fenbendazole.

Thread worms occur commonly in baby pigs. The adults are practically microscopic and live in the wall of the small intestine. Heavy infections may cause intensive scouring in neonatal pigs, resulting in acute dehydration. The threadworm (aka Strongyloides) lives in soil contaminated by infected feces. Unlike the other round worms of the intestine the threadworm larvae enter the pig by penetrating the skin or mucous membranes of the mouth and are transported by the blood to the lungs, coughed up and swallowed. They then develop to maturity in the small intestine. The infective larvae can also cross the placenta or be excreted by the colostrum and therefore infect piglets within 24 hours of birth. The prepatent period is from 3-7 days. Strongyloides ransomi is also particularly harmful for piglets. Massive infections cause hemorrhagic or mucous diarrhea, anemia and even sudden death. Other symptoms include coughing and abdominal pain.

Whipworms are another common parasite in pigs. This is another zoonotic parasite that can be transmitted to humans and other pets. In the United States, whipworms were one of the three most prevalent internal parasites of swine. The pigs pickup this parasite while grazing or rooting in the dirt. The adult worms are 5–6 cm long and whip-shaped; the anterior slender portion embeds within the epithelial cells of the large intestine, especially the cecum, with the thickened posterior third lying free in the lumen. Damage occurs to the pigs intestines with inflammation and lesions. Weight loss and diarrhea are symptoms of a whipworm infestation. Whipworms are easily treated with fenbendazole. Ivermectin has been used for whipworms with varying success.

External Parasites

Biting insects (hematophagous), i.e. they suck blood

- Black flies, gnats. Local problem in endemic regions, wordlwide, only on swine kept outdoors.

- Fleas. Local problem in livestock kept indoors by warm and humid weather, worldwide.

- Midges. Local problem in endemic regions, worldwide.

- Mosquitoes. A worldwide problem in all kind of livestock, but usually not the major issue. No issue in swine kept indoors.

- Stable flies. Can be a significant problem in swine kept outdoors by warm and humid weather, worldwide. No issue in swine kept indoors.

- Tsetse flies. A problem in Africa in all livestock kept outdoors.

- Horseflies. Usually a minor problem in all livestock kept outdoors by warm weather, worldwide. No issue in swine kept indoors.

- Houseflies. Can be a serious problem in swine operations worldwide, both indoors and outdoors, mainly in the warm and humid season.

- Filth & nuisance flies. Usually a secondary issue in swine operations, mainly in the warm and humid season.

- Lice. Very common problem worldwide, even in indoor operations, particularly during the cold season.

- Human bot flies, Dermatobia. A problem in many regions of Central and South America, only on swine kept outdoors.

- Screwworm flies. Usually not a very serious problem for swine, unless outdoors in endemic regions in tropical and subtropical countries.

- Wohlfahrtia. Occasionally a problem in Mediterranean countries during summer on swine kept outdoors

- Amblyomma ticks. A problem only for grazing pigs in tropical and subtropical regions, mainly America and Africa. Not an issue for industrial pig production.

- Dermacentor ticks. A problem only for grazing pigs during the war season. Not an issue for industrial pig production.

- Haemaphysalis ticks. A problem only for grazing pigs in tropical and subtropical regions, mainly in parts of Asia Africa and Europe. Not an issue for industrial pig production.

- Hyalomma ticks. A problem only for grazing pigs in tropical and subtropical regions, mainly in parts of Asia Africa and Europe. Not an issue for industrial pig production.

- Ixodes ticks. A problem only for grazing pigs in regions with moderate to cold climate, during spring and summer. tropical and subtropical regions, mainly America and Africa. Not an issue for industrial pig production.

- Rhipicephalus ticks. A problem only for grazing pigs in tropical and subtropical regions, mainly in Africa. Not an issue for industrial pig production.

- Mange mites. A problem worldwide in all kind of pigs, also indoors. Is found worldwide, but more frequent during the cold season in regions with temperate or cold climate.

Internal parasites

(endoparasites, worms, helminths)

The parasites' preferred location sites are indicated in brackets.

Gastrointestinal roundworms (nematodes)

- Ascaris suum. Pig roundworm. (Small intestine). Worldwide, more in tropical and subtropical regions.

- Globocephalus spp. Pig hookworm. (Small intestine). Worldwide, but regional incidence.

- Gnathostoma hispidum. (Stomach). Mainly Europe, Asia and Africa.

- Hyostrongylus rubidus. Red stomach worm. (Stomach). Worldwide, mostly in mixed infections.

- Mecistocirrus digitatus. (Stomach). Worldwide, more in warm and humid regions. Mostly in mixed infections.

- Oesophagostomum spp. Nodular worm. (Large intestine). Worldwide, mostly in mixed infections.

- Strongyloides spp. Threadworms, pinworms. (Small intestine). Worldwide, more in warm and humid regions.

- Trichostrongylus axei. (Stomach). Worldwide, mostly in mixed infections.

- Trichuris spp. Whipworms. (Large intestine). Worldwide.

- Metastrongylus spp. Pig lungworm. (Trachea, bronchi, bronchioles). Worldwide.

- Stephanurus dentatus. Kidney worm. (Kidneys). In tropical and subtropical regions.

- Suifilaria suis. (Skin). Southern Africa.

- Trichinella spp. (Muscles, small intestine). Worldwide.

- Dicrocoelium spp. Lancet fluke. (Bile ducts and gall bladder). A problem only for grazing pigs worldwide. Not an issue for industrial pig production.

- Eurytrema pancreaticum. Pancreas fluke. (Pancreatic ducts). In South America, Asia and África, in swine kept outdoors. Not an issue for industrial pig production.

- Fasciola gigantica. Giant liver fluke. (Liver tissue, biliary ducts and gallbladder). A problem only for grazing pigs worldwide. Not an issue for industrial pig production.

- Fasciola hepatica. Common liver fluke. (Biliary ducts and gallbladder). A problem only for grazing pigs worldwide. Not an issue for industrial pig production.

- Cysticercus cellulosae. Pork bladder worm. (Muscles). Worldwide in swine kept outdoors.

- Cysticercus tenuicollis. (Abdominal organs). Worldwide in swine kept outdoors.

- Echinococcus granulosus. Hydatid worm. (Various organs). Worldwide in swine kept outdoors.

Internal parasites: These must all use nutrients from the host to multiply and survive. They are found in the digestive tract, the kidneys, liver, lungs or the blood stream.

Types of parasitic worms of veterinary importance

There are three major types of helminths of parasitic importance, each one with similar anatomic characteristics and comparable life cycles:

An overview of these internal parasites can be found on the link below. Keep in mind, some of these internal parasites ARE transmissible to humans should something you ingest be contaminated with the larva.

Cysticercus cellulosae found in pigs is the intermediate stage of the tapeworm. Cysticerci in pigs are found in the brain, liver, heart and skeletal muscles. They cause an inflammatory response in the muscle and central nervous system. In humans, auto-infection can occur from the adult worm in the intestine. The most frequently affected site is the central nervous system.

Trichinella spiralis is a nematode which parasitizes pigs, dogs, cats, mice, wild boar and other carnivorous game, humans and other mammals. Larvae penetrate the epithelial lining of the small intestine, undergo four moults and become sexually mature adults. The adult worms are 1 – 4 mm long. The newborn larvae pass to the striated muscles by the lymphatics and the blood stream.

Sparganosis in pigs is seen in the Asia-Pacific region and some other parts of the world and is caused by spargana, the larval (plerocercoid) stages of the tape worm Spirometra erinacei. The adult tape worm Spirometra erinacei lives in the small intestine of the cat, fox and dog. The egg passed in the faeces develops into a ciliated coracidium in water, which when ingested by cyclops (the water flea), the first intermediate host, develops into a procercoid. If the cyclops with the procercoid is eaten by a frog, the second intermediate host, the procercoid develops into a plerocercoid which resembles the adult tape worm in miniature but without the genitalia. When these frogs are eaten by a cat, fox and dog the plerocercoid develops into mature tape worms - Spirometra erinacei. However, if a frog is eaten by a pig or other animals such as snakes the plerocercoid migrates to certain tissues, particularly the skeletal muscles where they appear as cysts up to 6 mm long or as ribbon like structures about 5 cm long with a miniature scolex. These are termed spargana. Humans can be infected with spargana.

Porcine babesiosis (Piroplasmosis, Texas fever, Red water, Tick fever) of swine, cattle, horses, sheep and swine is a protozoan disease caused by various species of protozoa in the genus Babesia. Babesiosis in swine is caused by B. trautmaniand B. perroncitoi. The percentage of parasitized erythrocytes may be up to 60 % in swine. Pregnant sows may abort. Abortion is associated with febrile animals. It is believed that the source of infection for domestic swine are often feral pigs.

Toxoplasmosis is contagious disease of swine, sheep and other species characterized with encephalitis, pneumonia and neonatal mortality. It is caused by protozoon Toxoplasma gondii in animals and humans. Toxoplasma is most frequently found in pigs and sheep. Young animals are infected to a lesser degree than old animals. Cattle are rarely affected with clinical toxoplasmosis. Young pigs may die from pneumonia caused by toxoplasmosis. Humans can get infected with Toxoplasma cysts by ingestion of uncooked animal tissue. In humans clinical symptoms may vary from fever, malaise, skin rash, pneumonia, myocarditis, lymphadenopathy and encephalitis. Infected pregnant women may transfer the tachyzoites to the fetus.

Direct and indirect life cycles

There are two major types of life cycles, depending basically on the number of host:

Routes of entry into the host

Infective stages of parasitic worms have several routes of entry into their hosts, whereby each species usually follows one of these routes:

Sources for above information:

http://www.thepigsite.com

http://parasitipedia.net/index.

http://www.merckmanuals.com

http://vetmed.iastate.ed

http://www.morrisvetcenter.com

http://www.merckmanuals.com/vet

http://www.merckvetmanual.com/parasites_of_pigs/strongyloides

http://www.vetnext.com

http://vetmed.iastate.edu/vdpam

http://vetmed.iastate.edu/vdpam/swine-diseases/kidney-worm-infection

Types of parasitic worms of veterinary importance

There are three major types of helminths of parasitic importance, each one with similar anatomic characteristics and comparable life cycles:

- Roundworms (nematodes). They belong to the group of Nemathelminthes. They look just like worms, more or less long and thick. Close to 30'000 species are known, more than 16'000 parasitic ones.

- Flukes (trematodes). They belong to the group of Platyhelminthes (= flat worms). There are about 20'000 species, most of them parasitic of mollusks and vertebrates. They often have an oval form.

- Tapeworms (cestodes). They belong also to the group of Platyhelminthes (= flat worms). About 1'000 species are known, all parasitic of vertebrates, including livestock, pets and humans.

- Protozoa (Protozoa) Protozoa are small single celled organisms that are found in the small and large intestine. There are four found in the pig of any significance, including coccidia, balantidium coli, cryptosporidia and toxoplasma. Of these, coccidia are the only one of importance and then normally only in the young pig.

An overview of these internal parasites can be found on the link below. Keep in mind, some of these internal parasites ARE transmissible to humans should something you ingest be contaminated with the larva.

Cysticercus cellulosae found in pigs is the intermediate stage of the tapeworm. Cysticerci in pigs are found in the brain, liver, heart and skeletal muscles. They cause an inflammatory response in the muscle and central nervous system. In humans, auto-infection can occur from the adult worm in the intestine. The most frequently affected site is the central nervous system.

Trichinella spiralis is a nematode which parasitizes pigs, dogs, cats, mice, wild boar and other carnivorous game, humans and other mammals. Larvae penetrate the epithelial lining of the small intestine, undergo four moults and become sexually mature adults. The adult worms are 1 – 4 mm long. The newborn larvae pass to the striated muscles by the lymphatics and the blood stream.

Sparganosis in pigs is seen in the Asia-Pacific region and some other parts of the world and is caused by spargana, the larval (plerocercoid) stages of the tape worm Spirometra erinacei. The adult tape worm Spirometra erinacei lives in the small intestine of the cat, fox and dog. The egg passed in the faeces develops into a ciliated coracidium in water, which when ingested by cyclops (the water flea), the first intermediate host, develops into a procercoid. If the cyclops with the procercoid is eaten by a frog, the second intermediate host, the procercoid develops into a plerocercoid which resembles the adult tape worm in miniature but without the genitalia. When these frogs are eaten by a cat, fox and dog the plerocercoid develops into mature tape worms - Spirometra erinacei. However, if a frog is eaten by a pig or other animals such as snakes the plerocercoid migrates to certain tissues, particularly the skeletal muscles where they appear as cysts up to 6 mm long or as ribbon like structures about 5 cm long with a miniature scolex. These are termed spargana. Humans can be infected with spargana.

Porcine babesiosis (Piroplasmosis, Texas fever, Red water, Tick fever) of swine, cattle, horses, sheep and swine is a protozoan disease caused by various species of protozoa in the genus Babesia. Babesiosis in swine is caused by B. trautmaniand B. perroncitoi. The percentage of parasitized erythrocytes may be up to 60 % in swine. Pregnant sows may abort. Abortion is associated with febrile animals. It is believed that the source of infection for domestic swine are often feral pigs.

Toxoplasmosis is contagious disease of swine, sheep and other species characterized with encephalitis, pneumonia and neonatal mortality. It is caused by protozoon Toxoplasma gondii in animals and humans. Toxoplasma is most frequently found in pigs and sheep. Young animals are infected to a lesser degree than old animals. Cattle are rarely affected with clinical toxoplasmosis. Young pigs may die from pneumonia caused by toxoplasmosis. Humans can get infected with Toxoplasma cysts by ingestion of uncooked animal tissue. In humans clinical symptoms may vary from fever, malaise, skin rash, pneumonia, myocarditis, lymphadenopathy and encephalitis. Infected pregnant women may transfer the tachyzoites to the fetus.

Direct and indirect life cycles

There are two major types of life cycles, depending basically on the number of host:

- Direct life cycles, with a single host that is called definitive or final host, where the worms reach maturity and reproduce. Roundworms often have direct life cycles.

- Indirect life cycles: with at least one obligate intermediate host in addition to the final host. Typical intermediate hosts are often small invertebrates such as snails, insects, crustaceans, etc. The worms complete certain development stages inside these intermediate hosts, with or without harming them. In some species the immature stages can multiply asexually inside the intermediate hosts. The final hosts get infected mostly by ingestion of infected intermediate hosts. Flukes (trematodes) and tapeworms (cestodes) often have indirect life cycles. Some species have even two obligate intermediate hosts (e.g. Dicrocoelium dendriticum).

Routes of entry into the host

Infective stages of parasitic worms have several routes of entry into their hosts, whereby each species usually follows one of these routes:

- Entry through a natural opening, mostly through the mouth, quite seldom through the anus, the nose, or other openings. Ingestion through the mouth is mostly passive, i.e. infective stages are ingested with contaminated food.

- Entry through the skin, either actively penetrating it by its own efforts, or passively through the bite of a vector(insects, ticks, etc.) that transmits infective stages. A special case is transplacental transmission, i.e. are those worms that can be from mothers to their young inside the uterus.

- Transmission from mother to their young can also occur through the mother's milk.

Sources for above information:

http://www.thepigsite.com

http://parasitipedia.net/index.

http://www.merckmanuals.com

http://vetmed.iastate.ed

http://www.morrisvetcenter.com

http://www.merckmanuals.com/vet

http://www.merckvetmanual.com/parasites_of_pigs/strongyloides

http://www.vetnext.com

http://vetmed.iastate.edu/vdpam

http://vetmed.iastate.edu/vdpam/swine-diseases/kidney-worm-infection